A Commentary on Québécois Separatism

‘The nationalist petty bourgeoisie is incapable of leading this revolution or even desiring it, because it is completely dependent on American imperialism, in whose hands – in the framework of Canadian Confederation, or in the future framework of a “sovereign” republic – it is only an obedient puppet … For [the exploited classes of Québec], separatism, along with the destruction of the capitalist structures, is the means for wrestling Québec from the clutches of American imperialism. It is a struggle for both the national liberation of Québec and the total social liberation of the Québécois.’

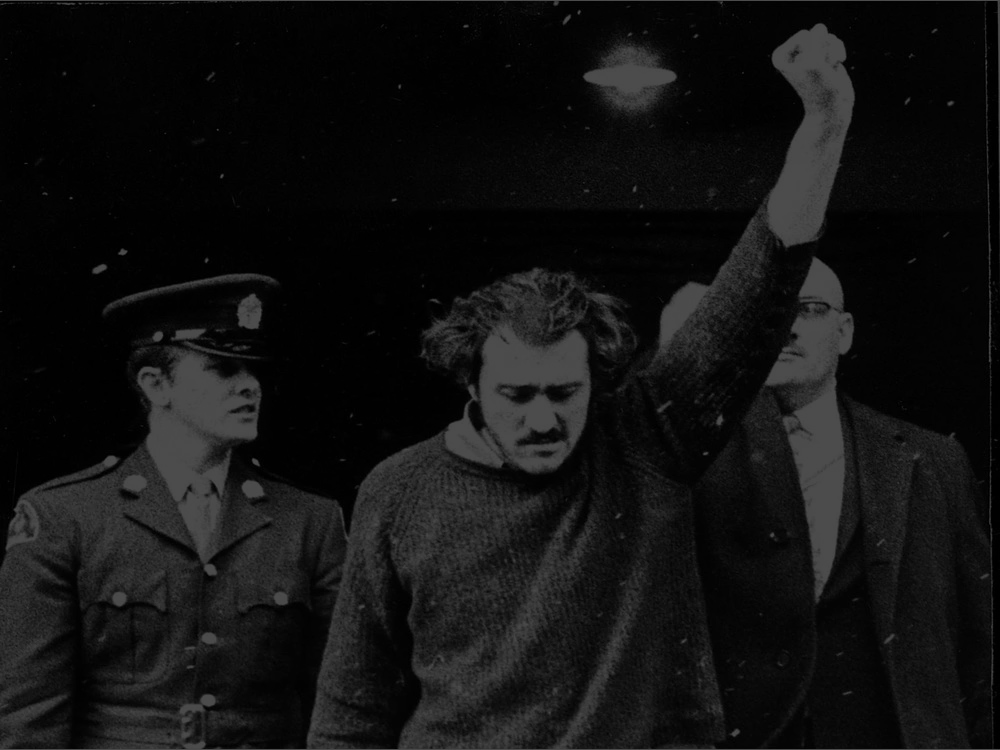

Pierre Vallières, White N—— of America

The issue of French Canada and its complicated, tumultuous relationship with English Canada has been ever-present in the minds of Canadians since Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War and its acquisition of New France. Yet, it is ultimately the partnership and union of these two peoples – however turbulent it may be at times – that embodies the quintessence of Canadian nationalism; if not just a simple line of defence standing in the way of Canada’s disappearance into the American Empire. Canadians are thus no stranger to the flaring nationalism of French-Canadians, and after some three-hundred years of debate, it seems as though English Canada has undertaken a tone of indifference – sometimes outright aggression.

In light of the Québec question and the sovereignty debate, English Canada is quick to dismiss Québec’s dissidence and continues to underplay the severity of the issue of independence. What they fail to see, however, is that the union of these two founding peoples forms the keystone of Confederation, and in the face of the looming American threat, the abandonment of one is the subversion of the whole. They fail to see that the true spirit of Canada lies in the hands of the Québécois, for the dying English Canadian nation, having been stripped of its culture, its heritage, and its very reason for existence, now serves as little more than a soulless extension of the odious Republic. The story of the Québécois is not one of self-determination; it is a matter of ensuring the survival of the old Canada. Its calls for independence are merely a provoked retaliation against the intolerable conditions of the English Canadian state; its cries for sovereignty merely a response to the betrayal of the core principles established in Confederation; and its dissidence is nothing more than a respectable fight against the Americanised, post-national Canada that makes Sir John A. Macdonald turn in his grave.

The key is this; there is no Canada without French Canada.

The history of Québécois separatism can be described as having gone through three main phases; the pre-Confederation era, the First Referendum era, and the Second Referendum era. Québec’s sentiments of independence and self-determination can be traced as far back as 1837 where, during the Lower Canada Rebellions, a group of French-Canadian separatists engaged in armed conflict with the British colonial government and unilaterally declared independence from British Canada as the Republic of Lower Canada. This rebellion, while extremely short-lived, laid the first foundations of the Québec sovereigntist movement. The leaders of the militias, many of whom fled to the United States, looked to establish a republican style of government that placed the needs of French Canadians at the very centre of their national ethos. The rebellions entrenched a certain ideal in the French-Canadian collective consciousness; an idea that French-Canadians, bonded by a common language, culture, and way of life, formed in themselves an entity separate from that of the British colonial nation. From this point on, the Lower Canada Rebellions, remembered by the Québécois as La Guerre de Patriotes (The Patriots’ War), would serve as Québec’s founding story; a time where the Québécois came together and proved themselves capable of greatness.

In the years following Confederation, however, it seemed as though Québec’s nationalist sentiments had largely died down. Under the leadership of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George Étienne-Cartier, the new Dominion of Canada began to take shape, with both founding peoples seeing themselves as equal partners in Confederation. Under Sir Macdonald’s National Policy and vision for the Canadian Pacific Railway, the Dominion experienced a great wave of prosperity and unity across both English and French Canada.

After Sir Macdonald’s death in 1891, the subsequent administration of Sir Wilfrid Laurier built upon the success of the first Prime Minister, adopting a strict policy of Canadianism and further emphasised the English-French partnership as a pillar of the Canadian nation. However, Sir Laurier’s administration also oversaw mass waves of European immigration to settle the Western territories; and while these efforts were highly necessary for maintaining the Dominion’s prosperity, it also had the effect of alienating the French-Canadian population by flooding the country with Anglophone or allophone immigrants. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 and the subsequent Conscription Crisis, the Québécois and French-Canadians began to question their place in Canadian Confederation.

The post-WW2 era saw the rise of Premier Maurice Duplessis in Québec, who is often seen as the last proponent of Québec’s ‘old nationalism’ which was heavily rooted in the traditions of the Catholic Church. His rule in Québec is remembered as ‘the Great Darkness’ due to his mildly authoritarian style of governance, his anti-Communist stances, and his extremely Conservative policies.

Following his death and the subsequent election of the Liberal government of Jean Lesage, Québec would undergo a period of massive sociopolitical change known as the Quiet Revolution, which facilitated the rise of a new form of Québec nationalism; one that did away with the old, right-wing, Catholic nationalism of Duplessis and one that created a renewed nationalist resistance that placed the preservation of the French language and of Québec culture above all else.

His policies clashed aggressively with those of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and created perhaps the most divisive, tense, and discordant period in Canadian history; a time where Canada struggled with a debilitative national identity crisis that made the Macdonald-Cartier visions of national unity seem a mere relic of an age long forgotten, a time where the nation suffered through a plethora of comprehensive issues ranging from decolonisation to modernisation to Americanisation; and a time where the bonds of Confederation that had thus far held the nation together for a hundred years seemed to be gradually fading away.

Lesage’s successor René Lévesque oversaw the creation of the nationalist Parti Québécois, establishing the sovereigntist movement as the dominant force in Québec politics and even allowing for the rise of homegrown domestic terrorism in the form of the Front de Liberation du Québec (FLQ). The tensions of this era culminated in Québec’s First independence referendum in 1980, which failed by a very slim margin and resulted in the defeat of the Parti Québécois. When the Parti returned to power in 1994, tensions were reignited in Québec, thus inciting a Second Independence referendum in 1995, which once again failed.

Sovereigntist sentiment is still highly prevalent in Québec today, and the spirit of the Québécois still remains unbroken. This Québécois regionalism/nationalism, while itself damaging to national unity, serves as a brilliant model for how the Canadian nation may be united. The Québécois are so fiercely defensive of their French-Canadian identity to such a point that they will actively oppose and fight against the influence of other cultures. This same spirit, this willingness to defend one’s culture, identity, heritage, and history – this notion must be inherited by the wider Canadian nation. Canadians must see themselves as Canadian first and Canadian above all else. Without this all-encompassing sense of national unity, Canada cannot continue to exist as a strong, independent nation. When this fire of national spirit is reignited, Canadians of all ages and backgrounds will experience a reinvigorating sense of patriotism.